Fundamental interaction

In particle physics, fundamental interactions (sometimes called interactive forces) are the ways that elementary particles interact with one another. An interaction is fundamental when it cannot be described in terms of other interactions. The four known fundamental interactions, all of which are non-contact forces, are electromagnetism, strong interaction, weak interaction (also known as "strong nuclear force" and "weak nuclear force" respectively) and gravitation. With the possible exception of gravitation, these interactions can usually be described in a set of calculational approximation methods known as Perturbation theory (quantum mechanics), as being mediated by the exchange of gauge bosons between particles. However, there are situations where perturbation theory does not adequately describe the observed phenomena, such as bound states and solitons.

Contents |

Overview

In the conceptual model of fundamental interactions, matter consists of fermions, which carry properties called charges and spin ±1⁄2 (intrinsic angular momentum ±ħ⁄2, where ħ is the reduced Planck constant). They attract or repel each other by exchanging bosons.

The interaction of any pair of fermions in perturbation theory can then be modeled thus:

- Two fermions go in → interaction by boson exchange → Two changed fermions go out.

The exchange of bosons always carries energy and momentum between the fermions, thereby changing their speed and direction. The exchange may also transport a charge between the fermions, changing the charges of the fermions in the process (e.g., turn them from one type of fermion to another). Since bosons carry one unit of angular momentum, the fermion's spin direction will flip from +1⁄2 to −1⁄2 (or vice versa) during such an exchange (in units of the reduced Planck's constant).

Because an interaction results in fermions attracting and repelling each other, an older term for "interaction" is force.

According to the present understanding, there are four fundamental interactions or forces: gravitation, electromagnetism, the weak interaction, and the strong interaction. Their magnitude and behavior vary greatly, as described in the table below. Modern physics attempts to explain every observed physical phenomenon by these fundamental interactions. Moreover, reducing the number of different interaction types is seen as desirable. Two cases in point are the unification of:

- Electric and magnetic force into electromagnetism;

- The electromagnetic interaction and the weak interaction into the electroweak interaction; see below.

Both magnitude ("relative strength") and "range", as given in the table, are meaningful only within a rather complex theoretical framework. It should also be noted that the table below lists properties of a conceptual scheme that is still the subject of ongoing research.

| Interaction | Current theory | Mediators | Relative strength[1] | Long-distance behavior | Range (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) |

gluons | 1038 |  (see discussion below) |

10−15 |

| Electromagnetic | Quantum electrodynamics (QED) |

photons | 1036 |  |

∞ |

| Weak | Electroweak Theory | W and Z bosons | 1025 |  |

10−18 |

| Gravitation | General Relativity (GR) |

gravitons (hypothetical) | 1 |  |

∞ |

The modern (perturbative) quantum mechanical view of the fundamental forces other than gravity is that particles of matter (fermions) do not directly interact with each other, but rather carry a charge, and exchange virtual particles (gauge bosons), which are the interaction carriers or force mediators. For example, photons mediate the interaction of electric charges, and gluons mediate the interaction of color charges.

The interactions

Gravitation

Gravitation is by far the weakest of the four interactions. Hence it is always ignored when doing particle physics. The weakness of gravity can easily be demonstrated by suspending a pin using a simple magnet (such as a refrigerator magnet). The magnet is able to hold the pin against the gravitational pull of the entire Earth.

Yet gravitation is very important for macroscopic objects and over macroscopic distances for the following reasons. Gravitation:

- is the only interaction that acts on all particles having mass;

- has an infinite range, like electromagnetism but unlike strong and weak interaction;

- cannot be absorbed, transformed, or shielded against;

- always attracts and never repels.

Even though electromagnetism is far stronger than gravitation, electrostatic attraction is not relevant for large celestial bodies, such as planets, stars, and galaxies, simply because such bodies contain equal numbers of protons and electrons and so have a net electric charge of zero. Nothing "cancels" gravity, since it is only attractive, unlike electric forces which can be attractive or repulsive. On the other hand, all objects having mass are subject to the gravitational force, which only attracts. Therefore, only gravitation matters on the large scale structure of the universe.

The long range of gravitation makes it responsible for such large-scale phenomena as the structure of galaxies, black holes, and the expansion of the universe. Gravitation also explains astronomical phenomena on more modest scales, such as planetary orbits, as well as everyday experience: objects fall; heavy objects act as if they were glued to the ground; and animals can only jump so high.

Gravitation was the first interaction to be described mathematically. In ancient times, Aristotle hypothesized that objects of different masses fall at different rates. During the Scientific Revolution, Galileo Galilei experimentally determined that this was not the case — neglecting the friction due to air resistance, all objects accelerate toward the Earth at the same rate. Isaac Newton's law of Universal Gravitation (1687) was a good approximation of the behaviour of gravitation. Our present-day understanding of gravitation stems from Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity of 1915, a more accurate (especially for cosmological masses and distances) description of gravitation in terms of the geometry of space-time.

Merging general relativity and quantum mechanics (or quantum field theory) into a more general theory of quantum gravity is an area of active research. It is hypothesized that gravitation is mediated by a massless spin-2 particle called the graviton.

Although general relativity has been experimentally confirmed (at least, in the weak field or Post-Newtonian case) on all but the smallest scales, there are rival theories of gravitation. Those taken seriously by the physics community all reduce to general relativity in some limit, and the focus of observational work is to establish limitations on what deviations from general relativity are possible.

Electroweak interaction

Electromagnetism and weak interaction appear to be very different at everyday low energies. They can be modeled using two different theories. However, above unification energy, on the order of 100 GeV, they would merge into a single electroweak force.

Electroweak theory is very important for modern cosmology, particularly on how the universe evolved. This is because shortly after the Big Bang, the temperature was approximately above 1015 K. Electromagnetic force and weak force were merged into a combined electroweak force.

For contributions to the unification of the weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, Abdus Salam, Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979.[2][3]

Electromagnetism

Electromagnetism is the force that acts between electrically charged particles. This phenomenon includes the electrostatic force acting between charged particles at rest, and the combined effect of electric and magnetic forces acting between charge particles moving relative to each other.

Electromagnetism is infinite-ranged like gravity, but vastly stronger, and therefore describes a number of macroscopic phenomena of everyday experience such as friction, rainbows, lightning, and all human-made devices using electric current, such as television, lasers, and computers. Electromagnetism fundamentally determines all macroscopic, and many atomic level, properties of the chemical elements, including all chemical bonding.

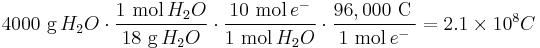

In a four kilogram (~1 gallon) jug of water there are  of total electron charge. Thus, if we place two such jugs a meter apart, the electrons in one of the jugs repel those in the other jug with a force of

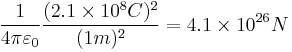

of total electron charge. Thus, if we place two such jugs a meter apart, the electrons in one of the jugs repel those in the other jug with a force of

This is larger than what the planet Earth would weigh if weighed on another Earth. The nuclei in one jug also repel those in the other with the same force. However, these repulsive forces are cancelled by the attraction of the electrons in jug A with the nuclei in jug B and the attraction of the nuclei in jug A with the electrons in jug B, resulting in no net force. Electromagnetic forces are tremendously stronger than gravity but cancel out so that for large bodies gravity dominates.

Electrical and magnetic phenomena have been observed since ancient times, but it was only in the 19th century that it was discovered that electricity and magnetism are two aspects of the same fundamental interaction. By 1864, Maxwell's equations had rigorously quantified this unified interaction. Maxwell's theory, restated using vector calculus, is the classical theory of electromagnetism, suitable for most technological purposes.

The constant speed of light in a vacuum (customarily described with the letter "c") can be derived from Maxwell's equations, which are consistent with the theory of special relativity. Einstein's 1905 theory of special relativity, however, which flows from the observation that the speed of light is constant no matter how fast the observer is moving, showed that the theoretical result implied by Maxwell's equations has profound implications far beyond electro-magnetism on the very nature of time and space.

In other work that departed from classical electro-magnetism, Einstein also explained the photoelectric effect by hypothesizing that light was transmitted in quanta, which we now call photons. Starting around 1927, Paul Dirac combined quantum mechanics with the relativistic theory of electromagnetism. Further work in the 1940s, by Richard Feynman, Freeman Dyson, Julian Schwinger, and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, completed this theory, which is now called quantum electrodynamics, the revised theory of electromagnetism. Quantum electrodynamics and quantum mechanics provide a theoretical basis for electromagnetic behavior such as quantum tunneling, in which a certain percentage of electrically charged particles move in ways that would be impossible under classical electromagnetic theory, that is necessary for everyday electronic devices such as transistors to function.

Weak interaction

The weak interaction or weak nuclear force is responsible for some nuclear phenomena such as beta decay. Electromagnetism and the weak force are now understood to be two aspects of a unified electroweak interaction — this discovery was the first step toward the unified theory known as the Standard Model. In the theory of the electroweak interaction, the carriers of the weak force are the massive gauge bosons called the W and Z bosons. The weak interaction is the only known interaction which does not conserve parity; it is left-right asymmetric. The weak interaction even violates CP symmetry but does conserve CPT.

Strong interaction

The strong interaction, or strong nuclear force, is the most complicated interaction, mainly because of the way it varies with distance. At distances greater than 10 femtometers, the strong force is practically unobservable. Moreover, it holds only inside the atomic nucleus.

After the nucleus was discovered in 1908, it was clear that a new force was needed to overcome the electrostatic repulsion, a manifestation of electromagnetism, of the positively charged protons. Otherwise the nucleus could not exist. Moreover, the force had to be strong enough to squeeze the protons into a volume that is 10−15 of that of the entire atom. From the short range of this force, Hideki Yukawa predicted that it was associated with a massive particle, whose mass is approximately 100 MeV.

The 1947 discovery of the pion ushered in the modern era of particle physics. Hundreds of hadrons were discovered from the 1940s to 1960s, and an extremely complicated theory of hadrons as strongly interacting particles was developed. Most notably:

- The pions were understood to be oscillations of vacuum condensates;

- Jun John Sakurai proposed the rho and omega vector bosons to be force carrying particles for approximate symmetries of isospin and hypercharge;

- Geoffrey Chew, Edward K. Burdett and Steven Frautschi grouped the heavier hadrons into families that could be understood as vibrational and rotational excitations of strings.

While each of these approaches offered deep insights, no approach led directly to a fundamental theory.

Murray Gell-Mann along with George Zweig first proposed fractionally charged quarks in 1961. Throughout the 1960s, different authors considered theories similar to the modern fundamental theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) as simple models for the interactions of quarks. The first to hypothesize the gluons of QCD were Moo-Young Han and Yoichiro Nambu, who introduced the quark color charge and hypothesized that it might be associated with a force-carrying field. At that time, however, it was difficult to see how such a model could permanently confine quarks. Han and Nambu also assigned each quark color an integer electrical charge, so that the quarks were fractionally charged only on average, and they did not expect the quarks in their model to be permanently confined.

In 1971, Murray Gell-Mann and Harald Fritsch proposed that the Han/Nambu color gauge field was the correct theory of the short-distance interactions of fractionally charged quarks. A little later, David Gross, Frank Wilczek, and David Politzer discovered that this theory had the property of asymptotic freedom, allowing them to make contact with experimental evidence. They concluded that QCD was the complete theory of the strong interactions, correct at all distance scales. The discovery of asymptotic freedom led most physicists to accept QCD, since it became clear that even the long-distance properties of the strong interactions could be consistent with experiment, if the quarks are permanently confined.

Assuming that quarks are confined, Mikhail Shifman, Arkady Vainshtein, and Valentine Zakharov were able to compute the properties of many low-lying hadrons directly from QCD, with only a few extra parameters to describe the vacuum. In 1980, Kenneth G. Wilson published computer calculations based on the first principles of QCD, establishing, to a level of confidence tantamount to certainty, that QCD will confine quarks. Since then, QCD has been the established theory of the strong interactions.

QCD is a theory of fractionally charged quarks interacting by means of 8 photon-like particles called gluons. The gluons interact with each other, not just with the quarks, and at long distances the lines of force collimate into strings. In this way, the mathematical theory of QCD not only explains how quarks interact over short distances, but also the string-like behavior, discovered by Chew and Frautschi, which they manifest over longer distances.

Beyond the Standard Model

Numerous theoretical efforts have been made to systematize the existing four fundamental interactions on the model of electro-weak unification.

Grand Unified Theories (GUTs) are proposals to show that all of the fundamental interactions, other than gravity, arise from a single interaction with symmetries that break down at low energy levels. GUTs predict relationships among constants of nature that are unrelated in the SM. GUTs also predict gauge coupling unification for the relative strengths of the electromagnetic, weak, and strong forces, a prediction verified at the LEP in 1991 for supersymmetric theories.

Theories of everything, which integrate GUTs with a quantum gravity theory face a greater barrier, because no quantum gravity theories, which include string theory, loop quantum gravity, and twistor theory have secured wide acceptance. Some theories look for a graviton to complete the Standard Model list of force carrying particles, while others, like loop quantum gravity, emphasize the possibility that time-space itself may have a quantum aspect to it.

Some theories beyond the Standard Model include a hypothetical fifth force, and the search for such a force is an ongoing line of experimental research in physics. In supersymmetric theories, there are particles that acquire their masses only through supersymmetry breaking effects and these particles, known as moduli can mediate new forces. Another reason to look for new forces is the recent discovery that the expansion of the universe is accelerating (also known as dark energy), giving rise to a need to explain a nonzero cosmological constant, and possibly to other modifications of general relativity. Fifth forces have also been suggested to explain phenomena such as CP violations, dark matter, and dark flow.

See also

- Quintessence, a hypothesized fifth force.

- People: Isaac Newton, James Clerk Maxwell, Albert Einstein, Richard Feynman, Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam, Steven Weinberg, Gerardus 't Hooft, David Gross, Edward Witten, Howard Georgi

Notes

- ^ Approximate. See Coupling constant for more exact strengths, depending on the particles and energies involved.

- ^ Bais, Sander (2005), The Equations. Icons of knowledge, ISBN 0-674-01967-9 p.84

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1979". The Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1979/. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

References

General readers:

- Davies, Paul (1986), The Forces of Nature, Cambridge Univ. Press 2nd ed.

- Feynman, Richard (1967), The Character of Physical Law, MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-56003-8

- Schumm, Bruce A. (2004), Deep Down Things, Johns Hopkins University Press While all interactions are discussed, discussion is especially thorough on the weak.

- Weinberg, Steven (1993), The First Three Minutes: A Modern View of the Origin of the Universe, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-02437-8

- Weinberg, Steven (1994), Dreams of a Final Theory, Basic Books, ISBN 0-679-74408-8

Texts:

- Padmanabhan, T. (1998), After The First Three Minutes: The Story of Our Universe, Cambridge Univ. Press, ISBN 0-521-62972-1

- Perkins, Donald H. (2000), Introduction to High Energy Physics, Cambridge Univ. Press, ISBN 0-521-62196-8

- Riazuddin (December 29, 2009). "Non-standard interactions". NCP 5th Particle Physics Sypnoisis (Islamabad,: Riazuddin, Head of High-Energy Theory Group at National Center for Physics) 1 (1): 1–25. http://www.ncp.edu.pk/docs/snwm/Riazuddin_Non_Standartd_Interaction.pdf. Retrieved Saturday, March 19, 2011.

|

|||||